OLYMPIC PENINSULA

(Last updated 1/18/01)

Washington State's Olympic Peninsula

contains four distinct types of forests. Giant Sitka spruce (left)

and western red cedar are dominant in the temperate rain forest

along the Pacific coast, where cool Alaskan ocean currents, prevailing

westerly winds, and moderate year-round temperatures produce abundant

winter rain and summer fog - from 140 to over 160 inches of precipitation

a year; sunlight filtered through the mosses and drooping boughs

(center) suffuses the forest with a greenish glow. Further inland

and at slightly higher elevations, the spruce disappears and Douglas

fir, western hemlock, bigleaf and vine maple, black cottonwood,

and an occasional grand fir dominate the drier lowland forest

(right). At still higher elevations, the western red cedar finally

disappears, marking the start of the montane forest zone.

The Olympic National Park contains

about 750 National Champions, the largest living specimen trees

of their species. The tallest Douglas fir, located along the South

Fork Hoh River Trail, is 298 ft high - elsewhere a huge fir log

(left) defines the direction of almost 250 feet of trail. A wood

fungus (right) speeds the decay of a snag - more than 5,000 species

of mushrooms have been found in the forests of the peninsula

The Olympic National Park contains

about 750 National Champions, the largest living specimen trees

of their species. The tallest Douglas fir, located along the South

Fork Hoh River Trail, is 298 ft high - elsewhere a huge fir log

(left) defines the direction of almost 250 feet of trail. A wood

fungus (right) speeds the decay of a snag - more than 5,000 species

of mushrooms have been found in the forests of the peninsula

Mosses, primarily common cat-tail and

coiled-leaf, and lichens, including common witch's hair and Methuselah's

beard, appear to hang from every branch in the heart of the rain

forest; the Hall of Mosses Nature Trail near the Hoh Visitors

Center is lined with almost unrecognizable moss-draped maples

(right)

Mosses, primarily common cat-tail and

coiled-leaf, and lichens, including common witch's hair and Methuselah's

beard, appear to hang from every branch in the heart of the rain

forest; the Hall of Mosses Nature Trail near the Hoh Visitors

Center is lined with almost unrecognizable moss-draped maples

(right)

The brighter sunlight along the river

produces a "forest" of maples, cottonwoods, and alders

along the banks of the Hoh River (left and center), and also along

the Skokomish River (right), located in the southeast corner of

the Park

The brighter sunlight along the river

produces a "forest" of maples, cottonwoods, and alders

along the banks of the Hoh River (left and center), and also along

the Skokomish River (right), located in the southeast corner of

the Park

A 17-mile long road climbs south into

the interior of the peninsula from Port Angeles; at higher elevations

the subalpine forest zone, marked by mountain hemlock, subalpine

fir, and Alaska cedar takes over (left). The road eventually leads

to the Hurricane Ridge Visitor Center, at 5242 ft (right)

A 17-mile long road climbs south into

the interior of the peninsula from Port Angeles; at higher elevations

the subalpine forest zone, marked by mountain hemlock, subalpine

fir, and Alaska cedar takes over (left). The road eventually leads

to the Hurricane Ridge Visitor Center, at 5242 ft (right)

A steep trail with spectacular views

that begins just beyond the Visitor's Center (left) leads to the

summit of Hurricane Hill (right), at 5757 ft barely above timberline

A steep trail with spectacular views

that begins just beyond the Visitor's Center (left) leads to the

summit of Hurricane Hill (right), at 5757 ft barely above timberline

Wildlife abounds in the area - a male

blue grouse (left) scampers along a well-worn path through the

tall grass; a mule deer (right) peers between the stunted trees

Wildlife abounds in the area - a male

blue grouse (left) scampers along a well-worn path through the

tall grass; a mule deer (right) peers between the stunted trees

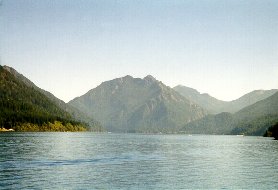

The Olympic Mountains form the north/south

backbone of the peninsula. Originally a series of volcanic seamounts

on the bottom of the ocean, as the Juan de Fuca plate approached

the rim of North America 35 million years ago, the seamounts were

jammed against the continental plate, fracturing, folding, and

stacking together to create the forerunner of today's Olympics.

Water and glaciers have since carved the basalt crags that remain.

Though not very high, the mountains are seldom climbed because

of their glaciation and inaccessibility; they are crowned by over

260 glaciers, and the highest of Mount Olympus' four peaks, West

- at 7965 ft, can only be reached by a 26 mile trek up the Hoh

River trail.

The Olympic Mountains form the north/south

backbone of the peninsula. Originally a series of volcanic seamounts

on the bottom of the ocean, as the Juan de Fuca plate approached

the rim of North America 35 million years ago, the seamounts were

jammed against the continental plate, fracturing, folding, and

stacking together to create the forerunner of today's Olympics.

Water and glaciers have since carved the basalt crags that remain.

Though not very high, the mountains are seldom climbed because

of their glaciation and inaccessibility; they are crowned by over

260 glaciers, and the highest of Mount Olympus' four peaks, West

- at 7965 ft, can only be reached by a 26 mile trek up the Hoh

River trail.

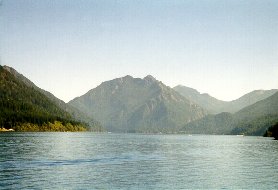

Glacier-carved Lake Crescent (left),

on the northern edge of the Olympic range, is a 10-mile long,

620 ft deep freshwater lake - 2650 ft Mount Storm King defines

its east end; the 90 ft plunge and horsetail of Marymere Falls

(right), just to the southeast of Storm King

Glacier-carved Lake Crescent (left),

on the northern edge of the Olympic range, is a 10-mile long,

620 ft deep freshwater lake - 2650 ft Mount Storm King defines

its east end; the 90 ft plunge and horsetail of Marymere Falls

(right), just to the southeast of Storm King

The Sol Duc ("magic waters")

River has carved its valley a few miles west of Lake Crescent;

a short hike from the trailhead just past the Hot Springs Resort

leads to the 60 ft triple plunge of Sol Duc Falls

The Sol Duc ("magic waters")

River has carved its valley a few miles west of Lake Crescent;

a short hike from the trailhead just past the Hot Springs Resort

leads to the 60 ft triple plunge of Sol Duc Falls

One of the most surprising and spectacular

features of the Park is its 60 miles of Pacific Ocean seacoast.

President Roosevelt managed to get the interior of the peninsula

designated as a National Park in 1938 - the bill passed by a single

vote in the Senate, but the coast was excluded despite the President's

wishes. Roosevelt then condemned or designated various coastal

segments as public works projects and placed them in the custody

of the Park Service, where they remained until 1953, when President

Truman added them to the Park by presidential proclamation. A

challenge to the proclamation mounted by the combined forces of

the Chamber of Commerce and the Park's superindendant on behalf

of logging interests followed, and was defeated only after Supreme

Court Justice William O. Douglas led a coalition of environmental

groups to defeat it in the media. The latest challenge has come

at the behest of oil companies who want to drill for oil offshore,

an effort supported by both the Reagan and Bush administrations,

and an issue still unresolved even though Congress made the offshore

area a Marine Sanctuary in 1988.

Second Beach is bounded by Quateata

and an offshore island wildlife refuge on the north (left); the

85-ft high Quillayute Needle and surrounding seastacks are the

Beach's centerpiece (right)

One of the most surprising and spectacular

features of the Park is its 60 miles of Pacific Ocean seacoast.

President Roosevelt managed to get the interior of the peninsula

designated as a National Park in 1938 - the bill passed by a single

vote in the Senate, but the coast was excluded despite the President's

wishes. Roosevelt then condemned or designated various coastal

segments as public works projects and placed them in the custody

of the Park Service, where they remained until 1953, when President

Truman added them to the Park by presidential proclamation. A

challenge to the proclamation mounted by the combined forces of

the Chamber of Commerce and the Park's superindendant on behalf

of logging interests followed, and was defeated only after Supreme

Court Justice William O. Douglas led a coalition of environmental

groups to defeat it in the media. The latest challenge has come

at the behest of oil companies who want to drill for oil offshore,

an effort supported by both the Reagan and Bush administrations,

and an issue still unresolved even though Congress made the offshore

area a Marine Sanctuary in 1988.

Second Beach is bounded by Quateata

and an offshore island wildlife refuge on the north (left); the

85-ft high Quillayute Needle and surrounding seastacks are the

Beach's centerpiece (right)

Weathered driftwood logs mark the high

tide line (left); Teahwhit Head (right) defines the south boundary

of the Beach

Weathered driftwood logs mark the high

tide line (left); Teahwhit Head (right) defines the south boundary

of the Beach

Tree-covered seastacks (left) and Hole-in-the-Wall

(right) mark the northern boundary of Rialto Beach

Tree-covered seastacks (left) and Hole-in-the-Wall

(right) mark the northern boundary of Rialto Beach

Towards sunset, the fog rolls in with

the tide and Rialto turns ghostly

Towards sunset, the fog rolls in with

the tide and Rialto turns ghostly

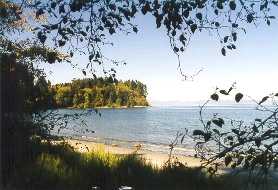

Outside the Park, most of the peninsula's

land is owned by logging companies and heavily clear-cut, even

on the many Indian reservations - almost the entire northern coast

is privately held, with little or no public access

Outside the Park, most of the peninsula's

land is owned by logging companies and heavily clear-cut, even

on the many Indian reservations - almost the entire northern coast

is privately held, with little or no public access

Long-billed dowitchers forage along

the 6-mile long Dungeness Spit, now a National Wildlife refuge,

near Sequim ("skwim") on the northeast coast - in the

rain shadow of the Olympics, the area gets less than 17"

of rain per year, compared to over 200" on Mt. Olympus 30

miles west. The New Dungeness Lighthouse (right), whose lamp was

first lit in December, 1857, now sits 1/2 instead of its original

1/6 of a mile from the tip of the Spit, thanks to the shifting

sands that maintain the Spit's existence

Long-billed dowitchers forage along

the 6-mile long Dungeness Spit, now a National Wildlife refuge,

near Sequim ("skwim") on the northeast coast - in the

rain shadow of the Olympics, the area gets less than 17"

of rain per year, compared to over 200" on Mt. Olympus 30

miles west. The New Dungeness Lighthouse (right), whose lamp was

first lit in December, 1857, now sits 1/2 instead of its original

1/6 of a mile from the tip of the Spit, thanks to the shifting

sands that maintain the Spit's existence

Named by Captain George Vancouver (for

the Marquis of Townshend) in 1792, the official dedication of

Port Townsend in the northeast corner of the Peninsula took place

on April 24, 1851; the city contains many Victorian buildings,

including the Starrett Mansion (left), built by George in 1889

as a wedding present for his wife Ann. The Point Wilson Lighthouse

(right) is located in Fort Worden State Park at the northeasterly

tip of the Peninsula

Named by Captain George Vancouver (for

the Marquis of Townshend) in 1792, the official dedication of

Port Townsend in the northeast corner of the Peninsula took place

on April 24, 1851; the city contains many Victorian buildings,

including the Starrett Mansion (left), built by George in 1889

as a wedding present for his wife Ann. The Point Wilson Lighthouse

(right) is located in Fort Worden State Park at the northeasterly

tip of the Peninsula

Return to

Home Page

Return to

Home Page